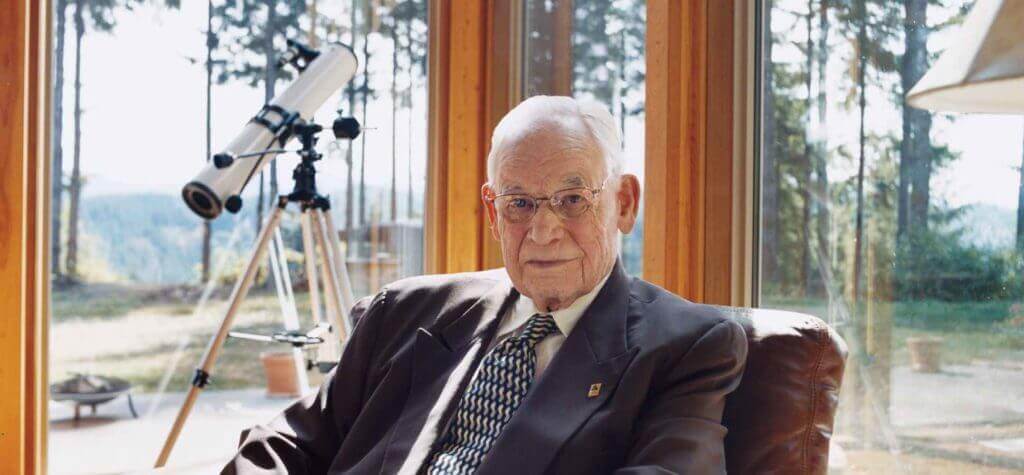

Sir Walter Lindal’s name may carry an aristocratic ring but his origins are anything but lordly. Born to hardscrabble Icelandic immigrants in 1919, he grew up on a wheat farm in Saskatchewan, Canada, with five brothers and sisters. (“Sir” is the translation of his given name, Sculi.) After his mother died, his father lost the farm and sent him and his twin brother to an orphanage. Despite this Dickensian background, the company he founded in 1945, Seattle-based Lindal Cedar Homes, is now the world’s biggest manufacturer of prefabricated cedar houses, with 193 employees and sales of $50 million last year. Prefab housing is a decidedly utilitarian concept, but Lindal gave it high-class appeal with innovative designs, top-quality materials, and deft marketing. Along the way he designed a machine gun, wrote a book, and racked up 17 patents.

I was five when we went to the orphanage. There were times when we went a couple of days without any food. I knew what hunger was. I lost my mother at two. She died of childbed fever–a doctor’s dirty hands. My dad kind of fell apart. He had a couple of crop failures and lost the farm. He had six kids to take care of.

My first venture was raising chickens. I was about 13 years old. We bought chicks for 4 cents each. We started the winter with 14 and the cold killed 10 of them so we only had four left. They were all good hens, though. We got to know them. One was called Rat-face because she looked like a rat. Another was Swollen Belly. We got four eggs a day on a good day, so three days to get a dozen, which we sold for 15 cents. Fifteen cents, in those Depression days, was a lot of money.

I became the usurer, or lender, of the school. A two-bit loan would be paid off for 35 cents. I’d get 10 cents interest.

I was always thinking of ideas and plans. If you make something, you have to sell it. You’re born with that, I think–none of the other boys had moneymaking ideas. They didn’t set up little gangs. We called ourselves gangs; today you’d say partnerships.

Coming out of school, there wasn’t any work–it was the Depression. I saw a want ad in the Winnipeg Free Press that said it had management possibilities. Turned out it was a job selling Fuller brushes. It was good training. I had to get out of some bad habits, though. I was a know-it-all teenager. I read Dale Carnegie’s book, How to Win Friends and Influence People, and I found out I was the bad guy, so I changed my ways. And my sales went up.

My Uncle Ben in Chicago ran a little lumberyard. He taught me the business. One day this young couple came in, and they wanted to buy wood for a whole house. The lady had this magazine clasped tight to her bosom. There was a picture of a home in there, but it was a castle–beyond anything they could afford. So the first thing I had to do was something our salespeople have to do, which was downsell ’em–their eyes were too big. I drew up a little design, and I gave ’em a price for the wood, and the plumbers, and the electricians, and I was able to put the whole package together. I was able to get them a 95 percent loan. We got a builder and in five months we had their home. That’s how it began. Selling a package.

After Canada got into WWII, I volunteered for the Canadian Army. It was a cruel war. I wanted to be an officer, but I didn’t have the qualifications–they required a college education–so I decided I had to do something spectacular. One way would have been to be a hero, but that wasn’t the idea–the idea was to survive. I was a good shot, but I didn’t like our machine gun. It was too top-heavy. It fired a .30-caliber round and weighed 16 pounds. I decided to design a better one. I knew that a smaller .25-caliber round could do the job, so I designed a gun with the smaller round. It fit 41 rounds instead of just 11 of the heavier bullets. I moved the magazine back. Put the weight so it was better balanced. Made things lighter, got it down to nine pounds. I got the designs all done and made a presentation. Next thing I knew I was summoned to Ottawa. They liked the weapon and within six months I was a captain.

Now I had a limo with a beautiful CWAC [Canadian Women’s Army Corps] driver, I had a secretary, and a desk, and an office. But there came a day when the general said, “We’re going to have to drop your machine gun. We think it’s great, but”–and he picked up a .30-caliber round–“the fact of the matter is, we have a trillion of these, and we’re not about to dump them in the sea.” So my great idea got washed down. Later I worked on an antiaircraft tank that could shoot down German planes.

During the war, I saw how the Army could build encampments that housed 25,000 men in a season thanks to mechanized production and prefabrication. We don’t like that word because it denotes something cheap and shoddy, so we say precut. I thought we could use the same idea for packaged homes. I picked Toronto as Canada’s fastest-growing city. But it’s a solid brick town–they don’t build wood houses in the city. So we were relegated to summer cottages and country homes.

When we started, the price for a basic package was $195. I designed the houses myself for most economical use of materials. We never thought of architecture or looks–not to begin with. Today the average price is more than $100,000. Customers want bigger and bigger houses–we’ve done homes as big as 15,000 square feet.

Why cedar? We felt it was the best wood. It had the attractive finish. Nice to work with. Didn’t decay. It had a reputation already. Fir is harder and stronger but it’s not as attractive as cedar.

Much as we love cedar, it’s not perfect. Two-thirds of its weight is water or sap. To pay the freight on all that water was crazy! We dried the wood in kilns–made it lighter and stronger. Soon it became obvious that the place to have the plant was where the cedar trees came from. So we packed the kids in the big black Cadillac and drove across the mountains to Vancouver, British Columbia, and set up a plant there. We moved once more, in 1966, to the States.

Our top salesman came to me–could he become an independent dealer? I thought, why not? Within a few years we had dealerships in Kingston, Montreal, and Ottawa. We became a dealer organization. We’ve got about 180 dealers all over the world.

We sell 400 to 500 homes a year. We sell a lot on the West Coast, the East Coast, Florida, and Hawaii. Japan, Korea, and Russia are big markets. Altogether we’ve sold almost 50,000 homes.

We made some mistakes. We didn’t bend to trends that should have been obvious. We tried to keep prices down and build small. But that’s not what people wanted. They wanted to go big. They didn’t mind going into debt for 30 years. It wasn’t my instinct, but that’s what they wanted. Of course, the basic elements that made a good small house–strong design, top-quality materials–worked for big houses, too. And it was more profitable for us. We built fewer units but our overall revenue went up.

My four kids own the company now. That was a smart decision. Now a new generation has taken over, and they are making more money than I ever made. I still hold a 4 percent share through a mathematical error.

I work every night, every Saturday, every Sunday. I enjoy it. I’m designing, I’m writing, I’m being creative. If it was drudgery, I would avoid it. I swim a quarter mile four days a week, I hike two and a half miles two days a week, and I rest on Sunday. There’s some satisfaction in accomplishing things. I can’t expect anybody to work as hard as I do.

Read more about the history of Lindal Cedar Homes